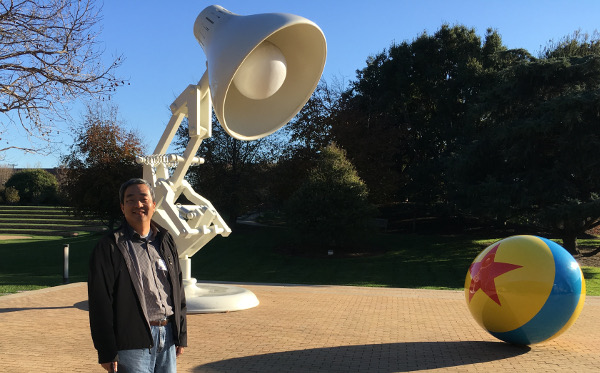

It was such a nostalgia seeing Luxo Jr. at Pixar Studio.

When I was in computer graphics, the industry leaders were Evans & Sutherland and Pixar; the show was SIGGRAPH. I attended the nerdy conference probably every other year. There were two main technological development directions then: photo-realistic rendering and 3D interactive graphics. (Later, when I exited the field, image processing and digital video became mainstream.) We understood the technologies cannot achieve both and this division was a compromise. Each side, then, sought inspirations from the other and tried to improve the state of the arts in partnership.

In 1984, Pixar produced a poster titled “1984 – Pool Balls.” It was mesmerizing to us graphics practitioners. I stared at the poster for hours and scrutinized every details: obviously the motion blurs, the reflective surfaces of the balls, the different shades of the felt and its realistic texture, and the physics of the ball movements. A rendering of that resolution took tremendous amount of computation and time. The break-through was a distributed algorithm that became part of the famed RenderMan program. Kids will come to me and asked about the poster. They expected artistic deep human meaning and I would have tried to explain the technologies and they would scurry away.

Normal SIGGRAPH short films were some boring tea pot rotating in various ways. Why tea pot? Simple, we engineers were lousy graphics modelers. Someone (Martin Newell) actually modeled the tea pot and make the file public domain. The Utah tea pot also became a de factor standard for rendering quality and speed.

In 1986 SIGGRAPH, Pixar showed the now famed Luxo Jr short-film. I was in the audience and felt like a teenager in a rock concert of my most loved band. The whole auditorium gave a standing ovation that lasted a long long time.

There were two light sources, cleverly the Luxo Jr and the little lamp. The lights played off the ball and lamps nicely. The physical modeling was flawless. The motions: jumps, bouncing of the balls, etc. were convincingly real. The film lasted about 2 minutes. For us computer graphics guys, that’s nearly 3000 frames at high resolution. Pixar had a break-through with rendering technologies to produce the film. But that’s not why we applauded.

The film was emotionally touching and told a nice story. Everyone in the audience understood that they just witnessed a historical moment: a fully computer generated motion picture was now within reach. If Pixar can produce Luxo Jr., a feature-length film was around the corner. That short film was a clear evidence that they had something none of us thought we needed: a real story teller — John Lasseter.

When I saw that Luxo Jr. statue in Pixar Studio in front of the Steve Jobs building, all those memories rolled back. Like the original Mickey Mouse of Walt Disney, Pixar remembered the significant break-through of that 2-minute short film 30 years ago. And I was there.