In 2006, I visited the village where my ancestors settled late in the Song Dynasty, about 800 years ago.

I found myself in a village where half the inhabitants shared my last name and probably more were my blood relatives. Every encounter began with a 15-minute session to figure out how we were related and what should be the proper way to address each other. There were books stacked up to chest-height recording the whole ancestral tree, all the way to the first settlers.

I met brothers and sister and heard their heart wrenching life stories. My father was on Chiang Kai-Shek’s side. For this reason, they were discriminated and persecuted for decades. They barely survived; many perished.

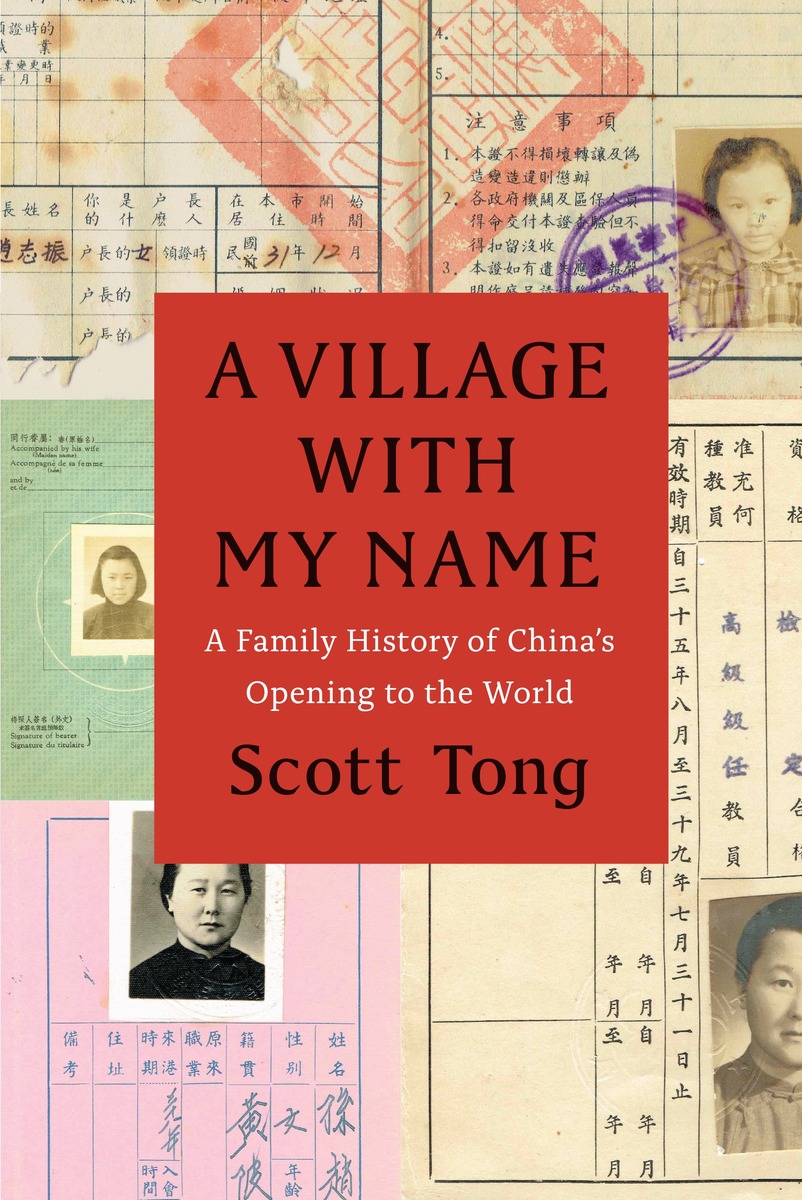

Scott Tong’s father had a story similar to mine. Scott, as a journalist, turned these stories into a book about that village where “everyone was named Tong.” He then did the same for his mother’s side.

I reacquainted with Scott in Beijing during his assignment, from Marketplace, in China. His father and I went way back. Without this connection, I would probably not have picked up this book. I knew those stories. Every family has their own version. What can you do? It was war. There is no war without tragedies, so traumatic that it take several generations to heal. Scott got it wrong. It was not shame they felt, it was pain. My brother, who was “on the wrong side of history,” choked up in tears when he told the stories of survival, suffering, and sacrifices. We then drank up in silence and changed to lighter and happier topics. It’s best that no one should experience those pains ever again. Let’s not talk about it anymore.

The holocaust survivors themselves don’t want to remember the pain. Their children understood and already knew the stories. It is up to the grand-children to turn those stories into history. This is a book for my and the future generations. Good job, Scott.